You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

-

The Fighting Cock is a forum for fans of Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. Here you can discuss Spurs latest matches, our squad, tactics and any transfer news surrounding the club. Registration gives you access to all our forums (including 'Off Topic' discussion) and removes most of the adverts (you can remove them all via an account upgrade). You're here now, you might as well...

Latest Spurs videos from Sky Sports

all those fuckers moaning about animal rights...well, i were doing that at my local park and i got arrested.

Thanks

existenzrippchen

appreciate the effort. Interesting read from a proper Spurs man

existenzrippchen

appreciate the effort. Interesting read from a proper Spurs man

This thread is unbearable

My favourite of all time

http://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/0/football/32917928

Champions League final: Steffen Freund - How I resisted the Stasi

By Steve CrossmanBBC World Service Sport

Berlin, venue for Saturday's Champions League final between Barcelona and Juventus, was a very different city 27 years ago. Then, with the Berlin Wall still standing, East Germany's secret police, the Stasi, would often target sports people as potential informants.

It's 1988 in the German Democratic Republic, known to most as East Germany, still over a year before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

A future German international and Champions League winner is thrown into a dark room in Brandenburg (an area which surrounds the German capital) before two men sit him in a chair, click on their torches and shine them directly into his eyes.

"You will work for the Stasi and tell us about your team-mates," the men say. "If you don't, your family will be in trouble."

Steffen Freund, then playing for Stahl Brandenburg, looks back at the agents of East Germany's fearsome secret police and says no. He is 17 years old.

Linked to Russia's infamous KGB security agency, the Stasi were regarded as one of the most effective intelligence agencies of the Cold War. They conducted surveillance on their own people and engaged in a process called Zersetsung - or "decomposition" - designed to mentally harass potential informants or those that might cause trouble for them.

But Freund, now 45, did not fall apart. "The power of the Stasi was massive," he recalls. "You can't imagine the pressure.

"They tried to build networks in football teams and they had all the information. If you went to Austria to play a friendly, they would find out which player was maybe thinking about not coming home and they would be stopped from travelling."

A wall outside the former Stasi building in Berlin is covered in graffiti in December 1989, the month after the Berlin Wall came down

As a young and talented footballer, Freund was one of very few people in the country who could travel beyond the Wall, let alone to another country.

That made him an obvious target for a state security service whose primary goal was to control society.

"At that age, to say no was hard," the former Borussia Dortmund, Tottenham Hotspur and Germany midfielder says. "Would you say no or yes?"

It is a dilemma the modern-day footballer can thankfully only imagine and making the decision was all the harder because the Stasi were not starting from scratch. They were building on a bedrock of propaganda years in the making.

"We were taught at school not to leave East Germany," Freund says. "'Don't go to West Germany' they would say, 'the people over there have no jobs'.

"We understood that the Soviet Union was our big brother and we were told, 'you don't need to go anywhere'."

With that ideology being hammered down at every turn, Freund admits to becoming suspicious of his team-mates, knowing they too would have been approached.

An unidentified official arranges old Stasi files in Berlin, in 2002. The Stasi kept tabs on East Germany's population via a network of citizens-turned-informants

One club, Dynamo Dresden, was rumoured to have 18 players working with the secret police.

"It was scary, but that was how it worked," Freund says. "The East Germans lived in fear. They'd be in contact with your friends, they knew everything about you. That's why a lot of people went to jail for nothing, maybe just for being in contact with West Germans.

"I still feel for those people," he says. "Disappointed isn't the right word, it's deeper than that."

Even now, we don't know everything there is to know about the Stasi. We know sportsmen like East German footballer Falko Gotz felt he was under such heavy surveillance that he fled, successfully, to the West in 1983. He received a one-year ban from Fifa, but continued his career with Bayer Leverkusen.

But shredded Stasi files still reside in the German capital, where the debate about whether or not they should be restored was revived last year as the nation marked 25 years since the fall of the Berlin wall.

Freund was fortunate. His brave decision to say no did not come at a cost.

"In the end they couldn't put me under enough pressure because my family was clean," he remembers. "I said to the men, 'I like East Germany but I can't look at my team-mates and tell you who would want to escape. I'd never do it because I have team spirit.'"

Only seven men played for both East Germany and the unified German national team. Freund is one of them.

Freund, who won Euro 96 with Germany and played in the 1998 World Cup, moved to Tottenham in 1998

He also has a Champions League winners medal from 1997 as part of the Borussia Dortmund squad - alongside German internationals such as Matthias Sammer, Jurgen Kohler, Andreas Moller and Karl-Heinz Riedle, plus Scot Paul Lambert - that became the first (and last) German side to win the cup on home soil.

With that history in mind, he is already one of the region's favourite sons. But he is keen to stress he holds no bad feeling toward his former home.

"We had enough food," he says. "There was no luxury but we were never hungry and we enjoyed living there."

That too makes him lucky, but he'll never forget the day that could have stopped in its tracks a career on its way to the top.

"I'm still surprised I said no," Freund says and shakes his head. "I still remember their last words. 'If you tell your family, you are in trouble and maybe your parents will go to jail.'.

"Then they switched off their torches and I went home."

You can listen to the full interview with Steffen Freund on the Sportsworld programme on BBC World Service on Saturday, 6 June.

Champions League final: Steffen Freund - How I resisted the Stasi

By Steve CrossmanBBC World Service Sport

Berlin, venue for Saturday's Champions League final between Barcelona and Juventus, was a very different city 27 years ago. Then, with the Berlin Wall still standing, East Germany's secret police, the Stasi, would often target sports people as potential informants.

It's 1988 in the German Democratic Republic, known to most as East Germany, still over a year before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

A future German international and Champions League winner is thrown into a dark room in Brandenburg (an area which surrounds the German capital) before two men sit him in a chair, click on their torches and shine them directly into his eyes.

"You will work for the Stasi and tell us about your team-mates," the men say. "If you don't, your family will be in trouble."

Steffen Freund, then playing for Stahl Brandenburg, looks back at the agents of East Germany's fearsome secret police and says no. He is 17 years old.

Linked to Russia's infamous KGB security agency, the Stasi were regarded as one of the most effective intelligence agencies of the Cold War. They conducted surveillance on their own people and engaged in a process called Zersetsung - or "decomposition" - designed to mentally harass potential informants or those that might cause trouble for them.

But Freund, now 45, did not fall apart. "The power of the Stasi was massive," he recalls. "You can't imagine the pressure.

"They tried to build networks in football teams and they had all the information. If you went to Austria to play a friendly, they would find out which player was maybe thinking about not coming home and they would be stopped from travelling."

A wall outside the former Stasi building in Berlin is covered in graffiti in December 1989, the month after the Berlin Wall came down

As a young and talented footballer, Freund was one of very few people in the country who could travel beyond the Wall, let alone to another country.

That made him an obvious target for a state security service whose primary goal was to control society.

"At that age, to say no was hard," the former Borussia Dortmund, Tottenham Hotspur and Germany midfielder says. "Would you say no or yes?"

It is a dilemma the modern-day footballer can thankfully only imagine and making the decision was all the harder because the Stasi were not starting from scratch. They were building on a bedrock of propaganda years in the making.

"We were taught at school not to leave East Germany," Freund says. "'Don't go to West Germany' they would say, 'the people over there have no jobs'.

"We understood that the Soviet Union was our big brother and we were told, 'you don't need to go anywhere'."

With that ideology being hammered down at every turn, Freund admits to becoming suspicious of his team-mates, knowing they too would have been approached.

An unidentified official arranges old Stasi files in Berlin, in 2002. The Stasi kept tabs on East Germany's population via a network of citizens-turned-informants

One club, Dynamo Dresden, was rumoured to have 18 players working with the secret police.

"It was scary, but that was how it worked," Freund says. "The East Germans lived in fear. They'd be in contact with your friends, they knew everything about you. That's why a lot of people went to jail for nothing, maybe just for being in contact with West Germans.

"I still feel for those people," he says. "Disappointed isn't the right word, it's deeper than that."

Even now, we don't know everything there is to know about the Stasi. We know sportsmen like East German footballer Falko Gotz felt he was under such heavy surveillance that he fled, successfully, to the West in 1983. He received a one-year ban from Fifa, but continued his career with Bayer Leverkusen.

But shredded Stasi files still reside in the German capital, where the debate about whether or not they should be restored was revived last year as the nation marked 25 years since the fall of the Berlin wall.

Freund was fortunate. His brave decision to say no did not come at a cost.

"In the end they couldn't put me under enough pressure because my family was clean," he remembers. "I said to the men, 'I like East Germany but I can't look at my team-mates and tell you who would want to escape. I'd never do it because I have team spirit.'"

Only seven men played for both East Germany and the unified German national team. Freund is one of them.

Freund, who won Euro 96 with Germany and played in the 1998 World Cup, moved to Tottenham in 1998

He also has a Champions League winners medal from 1997 as part of the Borussia Dortmund squad - alongside German internationals such as Matthias Sammer, Jurgen Kohler, Andreas Moller and Karl-Heinz Riedle, plus Scot Paul Lambert - that became the first (and last) German side to win the cup on home soil.

With that history in mind, he is already one of the region's favourite sons. But he is keen to stress he holds no bad feeling toward his former home.

"We had enough food," he says. "There was no luxury but we were never hungry and we enjoyed living there."

That too makes him lucky, but he'll never forget the day that could have stopped in its tracks a career on its way to the top.

"I'm still surprised I said no," Freund says and shakes his head. "I still remember their last words. 'If you tell your family, you are in trouble and maybe your parents will go to jail.'.

"Then they switched off their torches and I went home."

You can listen to the full interview with Steffen Freund on the Sportsworld programme on BBC World Service on Saturday, 6 June.

Great read. Thanks. What a strong character Steffen is. I wonder how many of today's pampered divas would have coped with the stuff he had to?http://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/0/football/32917928

Champions League final: Steffen Freund - How I resisted the Stasi

By Steve CrossmanBBC World Service Sport

Berlin, venue for Saturday's Champions League final between Barcelona and Juventus, was a very different city 27 years ago. Then, with the Berlin Wall still standing, East Germany's secret police, the Stasi, would often target sports people as potential informants.

It's 1988 in the German Democratic Republic, known to most as East Germany, still over a year before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

A future German international and Champions League winner is thrown into a dark room in Brandenburg (an area which surrounds the German capital) before two men sit him in a chair, click on their torches and shine them directly into his eyes.

"You will work for the Stasi and tell us about your team-mates," the men say. "If you don't, your family will be in trouble."

Steffen Freund, then playing for Stahl Brandenburg, looks back at the agents of East Germany's fearsome secret police and says no. He is 17 years old.

Linked to Russia's infamous KGB security agency, the Stasi were regarded as one of the most effective intelligence agencies of the Cold War. They conducted surveillance on their own people and engaged in a process called Zersetsung - or "decomposition" - designed to mentally harass potential informants or those that might cause trouble for them.

But Freund, now 45, did not fall apart. "The power of the Stasi was massive," he recalls. "You can't imagine the pressure.

"They tried to build networks in football teams and they had all the information. If you went to Austria to play a friendly, they would find out which player was maybe thinking about not coming home and they would be stopped from travelling."

A wall outside the former Stasi building in Berlin is covered in graffiti in December 1989, the month after the Berlin Wall came down

As a young and talented footballer, Freund was one of very few people in the country who could travel beyond the Wall, let alone to another country.

That made him an obvious target for a state security service whose primary goal was to control society.

"At that age, to say no was hard," the former Borussia Dortmund, Tottenham Hotspur and Germany midfielder says. "Would you say no or yes?"

It is a dilemma the modern-day footballer can thankfully only imagine and making the decision was all the harder because the Stasi were not starting from scratch. They were building on a bedrock of propaganda years in the making.

"We were taught at school not to leave East Germany," Freund says. "'Don't go to West Germany' they would say, 'the people over there have no jobs'.

"We understood that the Soviet Union was our big brother and we were told, 'you don't need to go anywhere'."

With that ideology being hammered down at every turn, Freund admits to becoming suspicious of his team-mates, knowing they too would have been approached.

An unidentified official arranges old Stasi files in Berlin, in 2002. The Stasi kept tabs on East Germany's population via a network of citizens-turned-informants

One club, Dynamo Dresden, was rumoured to have 18 players working with the secret police.

"It was scary, but that was how it worked," Freund says. "The East Germans lived in fear. They'd be in contact with your friends, they knew everything about you. That's why a lot of people went to jail for nothing, maybe just for being in contact with West Germans.

"I still feel for those people," he says. "Disappointed isn't the right word, it's deeper than that."

Even now, we don't know everything there is to know about the Stasi. We know sportsmen like East German footballer Falko Gotz felt he was under such heavy surveillance that he fled, successfully, to the West in 1983. He received a one-year ban from Fifa, but continued his career with Bayer Leverkusen.

But shredded Stasi files still reside in the German capital, where the debate about whether or not they should be restored was revived last year as the nation marked 25 years since the fall of the Berlin wall.

Freund was fortunate. His brave decision to say no did not come at a cost.

"In the end they couldn't put me under enough pressure because my family was clean," he remembers. "I said to the men, 'I like East Germany but I can't look at my team-mates and tell you who would want to escape. I'd never do it because I have team spirit.'"

Only seven men played for both East Germany and the unified German national team. Freund is one of them.

Freund, who won Euro 96 with Germany and played in the 1998 World Cup, moved to Tottenham in 1998

He also has a Champions League winners medal from 1997 as part of the Borussia Dortmund squad - alongside German internationals such as Matthias Sammer, Jurgen Kohler, Andreas Moller and Karl-Heinz Riedle, plus Scot Paul Lambert - that became the first (and last) German side to win the cup on home soil.

With that history in mind, he is already one of the region's favourite sons. But he is keen to stress he holds no bad feeling toward his former home.

"We had enough food," he says. "There was no luxury but we were never hungry and we enjoyed living there."

That too makes him lucky, but he'll never forget the day that could have stopped in its tracks a career on its way to the top.

"I'm still surprised I said no," Freund says and shakes his head. "I still remember their last words. 'If you tell your family, you are in trouble and maybe your parents will go to jail.'.

"Then they switched off their torches and I went home."

You can listen to the full interview with Steffen Freund on the Sportsworld programme on BBC World Service on Saturday, 6 June.

Wow!! Just one thing that jumped out at me...

...isn't that Facebook??

The Stasi kept tabs on East Germany's population via a network of citizens-turned-informants

...isn't that Facebook??

Except that the lemmings do it voluntarily nowWow!! Just one thing that jumped out at me...

...isn't that Facebook??

Except that the lemmings do it voluntarily now

Everyone for years would go on about 1984 coming true and the govt knowing everything about us, then the idiots do it to themselves and post constant updates about their location, actions, feelings... and sometimes bank details!

Futurama did a brilliant parody of it all in Season 6 - the Eye-PhoneEveryone for years would go on about 1984 coming true and the govt knowing everything about us, then the idiots do it to themselves and post constant updates about their location, actions, feelings... and sometimes bank details!

...and then encourage people to FOLLOW THEM! In my day, that was called STALKING... and as far as I remember, a punishable offence!!Everyone for years would go on about 1984 coming true and the govt knowing everything about us, then the idiots do it to themselves and post constant updates about their location, actions, feelings... and sometimes bank details!

We should break away and form our own independent state - only way forward...and then encourage people to FOLLOW THEM! In my day, that was called STALKING... and as far as I remember, a punishable offence!!

it must be so easy for burglars these days. people posting "off on holiday for 2 wks". then updates of them on the beach somewhere.

easy for employers to keep tabs on employees.

u also get idiots saying they hate there job & boss.

or post pics of them drinking all night. & then phone in sick with the 'flu'.

easy for employers to keep tabs on employees.

u also get idiots saying they hate there job & boss.

or post pics of them drinking all night. & then phone in sick with the 'flu'.

Last edited:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/0/football/32917928

Champions League final: Steffen Freund - How I resisted the Stasi

By Steve CrossmanBBC World Service Sport

Berlin, venue for Saturday's Champions League final between Barcelona and Juventus, was a very different city 27 years ago. Then, with the Berlin Wall still standing, East Germany's secret police, the Stasi, would often target sports people as potential informants.

It's 1988 in the German Democratic Republic, known to most as East Germany, still over a year before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

A future German international and Champions League winner is thrown into a dark room in Brandenburg (an area which surrounds the German capital) before two men sit him in a chair, click on their torches and shine them directly into his eyes.

"You will work for the Stasi and tell us about your team-mates," the men say. "If you don't, your family will be in trouble."

Steffen Freund, then playing for Stahl Brandenburg, looks back at the agents of East Germany's fearsome secret police and says no. He is 17 years old.

Linked to Russia's infamous KGB security agency, the Stasi were regarded as one of the most effective intelligence agencies of the Cold War. They conducted surveillance on their own people and engaged in a process called Zersetsung - or "decomposition" - designed to mentally harass potential informants or those that might cause trouble for them.

But Freund, now 45, did not fall apart. "The power of the Stasi was massive," he recalls. "You can't imagine the pressure.

"They tried to build networks in football teams and they had all the information. If you went to Austria to play a friendly, they would find out which player was maybe thinking about not coming home and they would be stopped from travelling."

A wall outside the former Stasi building in Berlin is covered in graffiti in December 1989, the month after the Berlin Wall came down

As a young and talented footballer, Freund was one of very few people in the country who could travel beyond the Wall, let alone to another country.

That made him an obvious target for a state security service whose primary goal was to control society.

"At that age, to say no was hard," the former Borussia Dortmund, Tottenham Hotspur and Germany midfielder says. "Would you say no or yes?"

It is a dilemma the modern-day footballer can thankfully only imagine and making the decision was all the harder because the Stasi were not starting from scratch. They were building on a bedrock of propaganda years in the making.

"We were taught at school not to leave East Germany," Freund says. "'Don't go to West Germany' they would say, 'the people over there have no jobs'.

"We understood that the Soviet Union was our big brother and we were told, 'you don't need to go anywhere'."

With that ideology being hammered down at every turn, Freund admits to becoming suspicious of his team-mates, knowing they too would have been approached.

An unidentified official arranges old Stasi files in Berlin, in 2002. The Stasi kept tabs on East Germany's population via a network of citizens-turned-informants

One club, Dynamo Dresden, was rumoured to have 18 players working with the secret police.

"It was scary, but that was how it worked," Freund says. "The East Germans lived in fear. They'd be in contact with your friends, they knew everything about you. That's why a lot of people went to jail for nothing, maybe just for being in contact with West Germans.

"I still feel for those people," he says. "Disappointed isn't the right word, it's deeper than that."

Even now, we don't know everything there is to know about the Stasi. We know sportsmen like East German footballer Falko Gotz felt he was under such heavy surveillance that he fled, successfully, to the West in 1983. He received a one-year ban from Fifa, but continued his career with Bayer Leverkusen.

But shredded Stasi files still reside in the German capital, where the debate about whether or not they should be restored was revived last year as the nation marked 25 years since the fall of the Berlin wall.

Freund was fortunate. His brave decision to say no did not come at a cost.

"In the end they couldn't put me under enough pressure because my family was clean," he remembers. "I said to the men, 'I like East Germany but I can't look at my team-mates and tell you who would want to escape. I'd never do it because I have team spirit.'"

Only seven men played for both East Germany and the unified German national team. Freund is one of them.

Freund, who won Euro 96 with Germany and played in the 1998 World Cup, moved to Tottenham in 1998

He also has a Champions League winners medal from 1997 as part of the Borussia Dortmund squad - alongside German internationals such as Matthias Sammer, Jurgen Kohler, Andreas Moller and Karl-Heinz Riedle, plus Scot Paul Lambert - that became the first (and last) German side to win the cup on home soil.

With that history in mind, he is already one of the region's favourite sons. But he is keen to stress he holds no bad feeling toward his former home.

"We had enough food," he says. "There was no luxury but we were never hungry and we enjoyed living there."

That too makes him lucky, but he'll never forget the day that could have stopped in its tracks a career on its way to the top.

"I'm still surprised I said no," Freund says and shakes his head. "I still remember their last words. 'If you tell your family, you are in trouble and maybe your parents will go to jail.'.

"Then they switched off their torches and I went home."

You can listen to the full interview with Steffen Freund on the Sportsworld programme on BBC World Service on Saturday, 6 June.

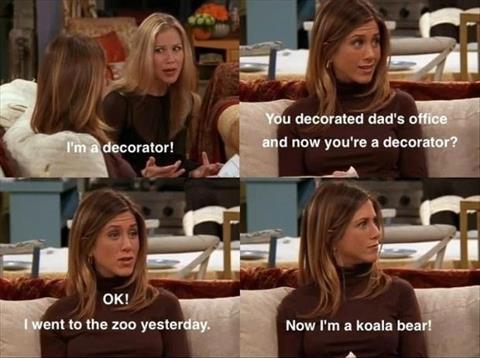

Poor Stefan - Escapes a regime of control and propaganda and the clutches of the diabolical secret police only to find himself in the grasp of...... BIG DUNC!!!

(any excuse to post this picture)

it must be so easy for burglars these days. people posting "off on holiday for 2 wks". then updates of them on the beach somewhere.

easy for employers to keep tab on employees.

u also get idiots saying they hate there job & boss.

or post pics of them drinking all night. & then phone in sick with the 'flu'.

Also encourages a complete lack of appreciation for punctuation and grammar. Stupid Facebook.

:townhmm: